Lutefisk

Norway

Some foods strike fear into the hearts of mortals; with each cautious bite we visualize the grim reaper taking us one step farther down the black velvet carpet towards a carriage drawn by the four horsemen of the apocalypse: fugu, poke salad, seso and lutefisk. Of the four, lutefisk is probably the least understood. The Norwegian cod delicacy has been eaten for so long that no one really knows how the unusual preparation came about; the process was most likely an invention of necessity and convenience. The cod is filleted and hung to dry where it ends up looking like a long strip of sycamore bark; these are bundled like wood for storage or transportation. It is the process of reconstituting the fish that frightens people – in Norway, the cod is soaked in plain water over a period of several days with the water replaced on a daily basis. The fish is then soaked in water with the addition of lye for several more days. You heard right, folks – lye, the old-time caustic component of laundry soap. Although many Norwegians will deny this, if the fish is left too long in the lye solution, the fish is inedible, and eventually the fat in the fish will be converted to soap which the Finnish call saippuakala (“soap fish”). During the lye soak the fish will swell to multiple times its original size; after the proper amount of time has passed the lutefisk is rinsed and soaked again for up to a week in plain water which is changed regularly. This is the epitome of a “kids don’t try this at home” dish – most people who prepare the fish do so from lutefisk carefully frozen and packed by trained professionals. Even when lutefisk is prepared properly, it is recommended that sterling silver cookware or utensils should not be used as the fish will ruin it. The fabulous explanations of how the dish was created truly are fish stories – they range from the Vikings invading Ireland having their dried fish poisoned but taking a liking to the caustic dish to the fish having caught fire on wooden racks and then cleaned to be eaten. The simplest explanation is usually the best – the lye helped make the dish go father by swelling it up (as it does for hominy); old recipes call for lye created using birch ash, limestone, and water. The same dried cod is exported from Norway for use in similar dishes using less caustic preparation such as baccalà (Italy) and bacalhau (Portugal).

Lutefisk has come to be known as a food of the people; where in the old days it was eaten all year round it can now be found on the menu primarily during the holiday season (November through Christmas). Lutefisk dinners are common in the U.S. in areas where there are large populations of Scandinavian immigrants such as Minnesota, however the Sons of Norway in Van Nuys, California host an annual lutefisk dinner that has been an tradition at the Norrøna Lodge for over 40 years. The lodge was founded in 1942, and they have been serving the dinner at their current location since 1956. For the dinner, the lodge sources its lutefisk from Olsen Fish Company in Minneapolis, Minnesota. The fish is caught and dried traditionally in Norway during the winter and then shipped to Olsen Fish Company where it is reconstituted. After the long reconstitution process, an average of 700 pounds of the lutefisk is then sold wholesale to the lodge, packed and shipped for the dinner. One of the lodge members (Bob Olsen) has been cooking the fish for 40 years, 30 of them at the annual dinner. Cooking lutefisk is an art that takes awhile to master – boil it too long and it literally turns into a gelatinous soup; not long enough and it becomes chewy. In addition to cooking up enough lutefisk to feed 400 people, the lodge also bakes 375 pounds of pork and beef Norwegian meatballs (and they are quick to point out that these are not Swedish – they’re better); the meatballs were formerly mixed with lamb, but are still made with breadcrumbs, dry milk, nutmeg and spices and individually hand-rolled. Each table is stocked with limpa (a Swedish rye bread, with citrus peel and anise) sourced from Berolina Bakery in Glendale, California and lefse, a traditional flatbread made from potatoes and served topped with butter and brown sugar. The meal also came with mixed vegetables, a fresh, light coleslaw and small boiled potatoes. Dessert was on the table even before the meal was brought out – each setting featured a cup of creamy rice pudding with sugar, butter, whipped cream and lingonberry sauce with a rolled krom krage cookie on the side.

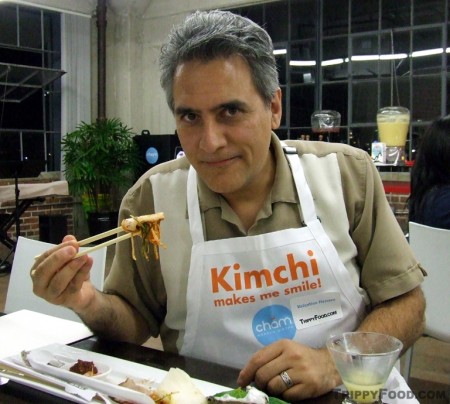

Dinner is served communal style at big round tables. In case you assume that the consuming of lutefisk is somewhat hazardous to your health, consider that the majority of the people attending their dinners were probably septuagenarians and older, and these people could put away the lutefisk like it was going out of style (or being banned). Two of the “younger” people at our table matched us fish for fish – we easily knocked back six or seven fillets each. The taste was remarkably mellow, although there was a slight chemical aftertaste. Lutefisk is rumored to have an offensive odor, but it wasn’t present in this case. The texture of the fish on the platters varied, and I found that I preferred it slightly mucilaginous where it dissolved on the tongue with no chewing required; it was easy to identify simply by shaking the platter. The traditional sauce of choice is simply clarified butter, but in recent times a less traditional cream sauce with nutmeg has been used and gravy boats of the creamy topping were provided at each table. Eddie Lin (who I had joined for dinner) referred to the lutefisk as “poor man’s lobster” because of the texture of the firmer preparation, although lutefisk and monkfish (the original “poor man’s lobster”) now are pricier than American lobster. I asked someone at the table what the proper traditional method of prepping the lefse was – it involved smearing a small pat of butter and sprinkling brown sugar on top, but one of our fellow diners went renegade and poured the clarified butter over an anthill of brown sugar to where you could barely see the lefse.

After dinner we walked out behind the dining hall where Scandinavian gifts were available for purchase as well as a bar where one could purchase a shot of traditional after-dinner aquavit (akvavit). This golden beverage is made from potatoes similar to vodka with a 40% alcohol kick. Akvavit is enhanced with a variety herbs, spices, and fruit extract, but smooth as the drink is it is all business. The drink takes on more of a golden color as it ages in oak. The general rule of thumb is that the darker the color, the longer it has been aged, or it has been aged in “young” casks with more resin content, although some aquavit uses artificial coloring. Lutefisk is not the kind of thing you’d want to eat on a daily basis, but at the annual Sons of Norway lutefisk dinner I think I may have redefined the term “all-you-can-eat”. Ryan (one of the younger cooks in the kitchen) was wearing and embroidered apron that read, “Take the risk – try lutefisk”, and I couldn’t agree more. Don’t let fear or rumors prevent you from experiencing this tasty and unusual dish. The taste, texture and experience of sharing this special meal with the members of the Norrøna Lodge is something I won’t soon forget – I’ll be back next year and that’s no lye.

Sons of Norway

Norrøna Lodge #50

14312 Friar Street

Van Nuys, California 91401

GPS Coordinates: 34°11’7.96″N 118°26’41.51″W

See images from the annual Sons of Norway lutefisk dinner at the Norrøna Lodge in Van Nuys, California

NOTE: This cost for this meal was provided by Norrøna Lodge #50. The content provided in this article was not influenced whatsoever by the organizer of the event.